A Question Of Perspective

By Yosha Gargeya & Mikkel Brok-Kristensen

Why taking an ecology-based approach to research in health care is vital

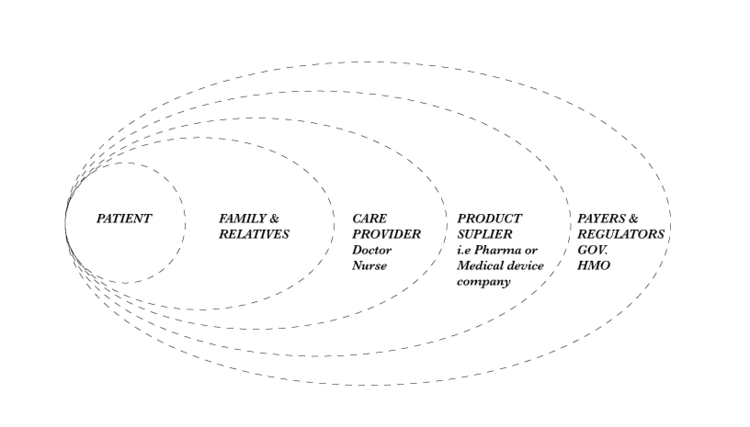

An illness has one patient but many stakeholders: the doctor who diagnoses, the nurse who provides care, the loved ones who support, the biotech companies that find new cures and treatments, and the payers who cover treatment costs. The best way to understand an illness – and how it should be diagnosed, treated and managed – thus acknowledges the ecology in which it takes place, and involves the collection and understanding of multiple perspectives.

Most of our work in health care involves new research and our approach to it always involves more than just one stakeholder, taking several stakeholders in the specific disease ecology into account. In our experience, it is through understanding different stakeholders’ perspectives that new insights can be found and new solutions developed thereafter.

Our work on a project covering a chronic progressive disease illustrates this best. Instead of focusing on the individual patients affected by the disease, we focused our research on individual clinics and their stakeholder ecologies, so we might understand the disease from a holistic perspective.

We spoke with patients and their families, as well as the doctors and nurses who provided care to these patients. Because of this, we were able to study not just the viewpoints of these stakeholders, but also how their viewpoints connected (or failed to connect) within their specific ecologies. In one clinic we found a particularly tightly woven ecology – the doctor and nurse were married. These matrimonial ties, however, did not change the fact that they, like most other doctors and nurses working side-by-side, had their own individual perspectives:

Dr. Hart’s perspective:

“We want to be scientists… to be meticulous.”

Dr. Hart was drawn to the discipline, and to a university hospital in particular, by his love for the mechanics and biochemistry that are central to his specialty. He was an enthusiastic practitioner of various tests that determine disease progression. While many other doctors we met were hesitant to use these measures because they felt the tests were cumbersome, outdated, or unnecessary, Dr. Hart maintained that they were crucial to his understanding of the patient’s state. He developed his own programs within the clinic’s medical records system to quickly document and measure disease-state markers and felt that these extra steps provided him with deeper patient insight.

Nurse Hart’s perspective:

“He [Dr. Hart] misses things… patients sit here with me for hours every month for treatment. We talk about treatment and when that is going well, the conversation is about everything else. And that conversation is just as important for care.”

Treatment for this disease, near its most progressed state, often entails daylong sessions with a nurse or physician’s assistant. Nurse Hart runs these sessions —giving her a direct line into the daily lives of patients. In comparison, she calls Dr. Hart’s consulting sessions “quick interruptions.”

One day a patient came into the clinic with severe symptoms that had resurfaced. Pain that Dr. Hart thought he had addressed emerged again, seemingly from nowhere —he was worried the patient had progressed and that he would have to change treatment strategies.

Nurse Hart, however, had spent the day treating this patient and learned that the patient’s daughter had recently gotten married – resulting in an unusual amount of activity for the patient since their last visit. It seemed likely to Nurse Hart that this pain was caused by stress and overexertion, rather than disease progression. This was a view that the patient never had the chance to express to the doctor and that could never have been captured in Dr. Hart’s tests —yet one that would ultimately alter the course of treatment.

Rachel, the patient:

“I have to go for quality of life, not quantity. You have to, or you’d drive off a bridge.”

In meeting patients we saw the disease as experienced —a constant ache at best, debilitating pain at its worst. Good days were those in which patients made plans to take their children out, went to fairs, and worked demanding hours. On bad days, however, just getting out of bed felt like a task of Herculean proportions and simple activities like braiding their children’s hair were impossible.

For patients, this results in an inability to predict what each day will bring prior to waking up. Making plans in advance seems futile, and the time horizon of a patient’s outlook is often limited to the following day.

Taking the ecology approach enables you to connect the dots and deliver solutions that all stakeholders can embrace.

By talking to different stakeholders within the same ecology, we can generate rich data about how an illness affects a variety of people. Just as importantly though, we are able to compare the perspectives of each stakeholder and appreciate the benefits and shortcomings of each.

Some perspectives paint the picture of the disease to be treated in broad strokes (like Hart’s progression tests). Others focus on the minutiae of day-to-day living (wedding seating charts and braiding hair). Doctors see patients quarterly for a fifteen-minute consultation and while they have an unparalleled overview of the patient’s disease state, they may miss the day-to-day ebbs and flows that are of most concern to patients. Nurses on the other hand, may have a fuller insight into the daily life of the patient but often lack the overview of disease progression, and (depending on local regulations) may be barred from prescribing drugs. Finally, patients who are ultimately best placed to describe the day-to-day progression of their disease in a way that sheds valuable insight into their condition are often unable to translate this in a relevant way to their doctors.

Identifying the blind spots in each perspective is vital to good research. Once blind spots are identified, they can also be eliminated. Integrating the varied perspectives of different stakeholders can thus be a driving force behind improving outcomes. It enables the development of solutions that can thrive in the context of each stakeholder, whether by developing treatments that embrace the different perspectives of each stakeholder or by creating new and more meaningful ways to reach out to and educate patients and caregivers.

Meeting with doctors, nurses, and patients who are not connected within a single ecology can still generate rich data but can impede the comparison of perspectives. Although it is important to focus on the medical expert at the top of the treatment hierarchy, it is also important to focus on the ongoing experiences of the patient. Beyond this, holding different perspectives alongside one another allows us to understand how they exist independently of each other while, at the same time, depending on each other in a web of cultural and social praxis. Individual fragments of these ecologies still yield compelling snapshots but may miss the bigger picture. That bigger picture contains vital insights for developing initiatives that can improve patient outcomes.

[Banner image by Chinnapong, via Shutterstock]