128-Bit Essence

"128-Bit Essence" explores the evolving interplay between human-, mass media-, and AI-generated representations through two units of analysis in the ethnographers’ toolkit - “Place” and “Person.” The installation consists of 64 artifacts each – representing Santa Monica and a single ethnographic informant, respectively – organized into two 8x8 grids. In lieu of an ethnographer’s narrative structure, the grids, mirroring the spatial organization of ‘bits’ in computing, flatten the artifacts’ relationships to one another and traditional hierarchies between human- and AI-generated materials.

Representation is core to ethnographic theory and practice. This installation challenges us to reconsider how ethnography and ethnographic objects of study are increasingly mediated by a range of new representational technologies, in particular Generative AI. The interplay of representations conjures what Malinowski termed “the imponderability of actual life,” the uncomfortable and political space between what we can represent and life as it is lived. Rather than resolving that tension, we invite you to critique, embrace, reject, and engage with the incongruencies and vulnerability that come with ethnographic representation.

In conversation with the EPIC 2024 themes of Foundation, Generation, and Displacement, we use visual representation to show how technologies can generate new ways of seeing by displacing old conventions, while at times reinforcing tropes and associations. As you walk through this space, we invite you to critique and embrace the incongruencies that come with representation, simultaneously a source of tension and a part of who and where we are as ethnographers.

This piece was prepared as a physical installation for the EPIC 2024 conference in Los Angeles. The online format differs from the physical, but has been provided to enable further information on the images included, available by clicking on individual images.

Place

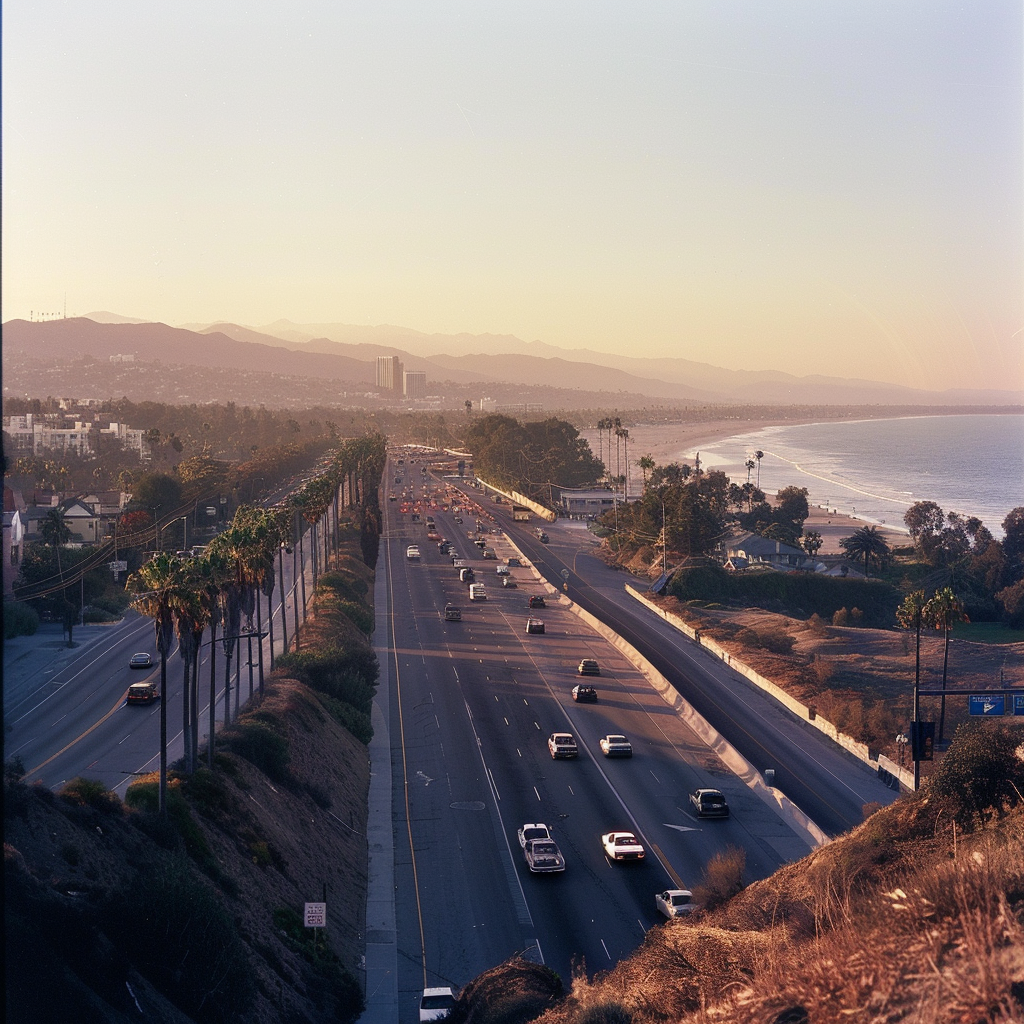

“Place” explores (versions of) Santa Monica, home to the EPIC 2024 conference. Photos of Santa Monica train AI models to portray this place, which in turn trains us humans as new vehicles for documentation and data gathering, completing the endless cycle of (re)presenting. The result is a piece that lives on a tenuous line between perception and stereotype, truth and humor, fact and fiction, subjective experience and universal abstraction. The piece functions as a simulacrum: a copy of a place that has no original source.

For the two artists, one of them a native Angeleno and the other never having been to Santa Monica, triangulating between different modes of mediation was a way to (re)discover Santa Monica. To generate the installation, one of the artists drew from personal experiences of Santa Monica while the other inhabited the vantage point of AI itself by experiencing Santa Monica solely through digital media, finding and producing images that aim to on the one hand represent the familiar and on the other hand discover the unfamiliar.

As AI systems mediate our work and our world further, we are forced to reckon with our own experiences of Santa Monica: Is it the wide car lanes and beautiful sunsets? Is it the dinosaurs roaming empty promenades or crystallized as fountains? Is it the messy overlaps of people, buildings, and the photographers’ gaze?

Film: Lords of Dogtown

Prompt: oceanfront park in Santa Monica with skyscraper nearby

Original photo

Prompt: Santa Monica architecture

Prompt: Santa Monica California Incline

Prompt: Santa Monica palisades park

Prompt: Santa Monica roundabout on a lush, tree-lined street, shown at street-level, first-person view, with cars moving down the street

Original photo

Film: The Sting

Prompt: oceanfront park in Santa Monica with skyscraper nearby

Prompt: Santa Monica farmer’s market

Original photo

Prompt: Santa Monica Third Street Promenade dinosaur fountains, running water, seen from below

Film: Point Blank

Prompt: Santa_Monica hotel tall white hanging over the edge of a cliff over Pacific Coast Highway

Original photo

Prompt: Santa Monica Third Street Promenade dinosaur topiary fountains, running water

Prompt: Endemic species of Santa Monica

Original photo

Prompt: Santa Monica public library and park

Film: Her

Original photo

Prompt: Santa Monica retail shops on street, verdant exteriors, 1950s and 60s architectural details

Prompt: 100 Wilshire Blvd Santa Monica

Original photo

Prompt: her (2013) movie still, Santa Monica pier

Prompt: Santa Monica pedestrian walkways over pacific coast highway

Prompt: The streets of Santa Monica

Prompt: The Sting (1973) movie still, Santa Monica Pier

Original photo

Prompt: Santa Monica Ocean Park

Original photo

Prompt: The streets of Santa Monica

Prompt: Santa Monica 3rd Street Promenade

Original photo

Prompt: Santa Monica retail shops on street, verdant exteriors, 1950s and 60s architectural details

Original photo

Prompt: the ethnographer in Santa Monica

Original photo

Prompt: Santa Monica roundabout on a lush, tree-lined street, shown at street-level, first-person view, with cars moving down the street

Film: Speed (1994)

Original photo

Prompt: Santa Monica retail shops on street in present day, brick walls covered by lots of green plants and hedges, buildings from 1950s and 60s

Prompt: Speed (1994) movie stills, Santa Monica bus

Prompt: Santa Monica public library and park

Prompt: Tourists in Santa Monica

Prompt: Santa Monica beach volleyball courts along the highway

Original photo

Original photo

Prompt: Santa Monica mountains

Original photo

Film: Barbie

Original photo

Original photo

Prompt: Santa Monica

Original photo

Prompt: Point Blank movie still, huntley hotel building, Santa Monica

Prompt: Santa Monica Ocean Park

Prompt: santa monica dogtown, everyday life

Film: The Big Lebowski

Original photo

Prompt: Santa Monica retail shops on street, verdant exteriors, 1950s and 60s architectural details

Person

"Person” takes the process of ethnographic representation and turns it on its head: the text of fieldnotes from an ethnographic encounter is used to generate a synthetic set of images representing a single informant’s struggles with air pollution. We see 64 representations of ‘Franck’ – a Martinique-born Parisian, father of two, avid runner, and transport manager – filtered through multiple layers of interpretation and representation, from the ethnographer to GPT4 to Midjourney to the artists.

While they fail as portraits – Franck is physically never the same – these representations take us into Franck’s everyday realities and to impossible places – episodes in his past, distant places outside the ethnographer’s reach, his dreams. In composite, they are a powerful affective portrait of how Franck encounters a polluted world: the experiences that shaped him, his anxieties and nervous habits, and his efforts to cope.

Yet these representations also obscure his experiences. To ‘paint a picture’ of his life, they rely on pastiche, collapsing familiar corners into globally famous landscapes; they misrepresent his physical self and race; they over-dramatize subtle or ambiguous experiences with established styles and iconography. The ethnographer’s eye for the complexity of everyday life is lost.

While some are absurd misunderstandings or hallucinations, many are gaps in precision met with leaps in interpretation, or gaps in data met with unknowing substitutions. As we collaborate more with AI systems, is this affective essence enough? Will we need greater ethnographic precision to make AI tools useful? Will models need to map the world better to reflect an ethnographer’s nuance?

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck taking up sports again 3-4 years ago, training for various competitions to stay mentally and physically fit. Show Franck running with a group of friends, avoiding heavily polluted areas with lots of cars. Illustrate their discussion about the importance of running at times with fewer cars to minimize pollution exposure. Depict them running early in the morning and late in the evening during the week, and checking air quality measures for weekend runs. Capture the camaraderie and determination of the group, with a backdrop of a cityscape that highlights both clean and polluted areas.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Create a photograph of Franck, an avid runner in Paris, who has become increasingly concerned about the city's pollution. Show Franck running with his friends, highlighting his awareness of the need to avoid polluted areas. Include a scene of his youngest daughter, who developed chronic bronchitis due to pollution, with Franck looking worried and protective. Capture the urban environment of Paris, hinting at the pollution, and emphasize Franck's concern for the air quality his daughters might face in the future.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene depicting Franck's evolving awareness of air pollution in Paris. Show Franck initially only noticing pollution when driving behind a truck, but then capturing the moment he sees traffic signs on the Péripherique highlighting pollution issues. Illustrate his enthusiastic, slightly exaggerated perception shift as he starts to see pollution everywhere--from the color of the sky to changes in the weather. Depict Paris with a hazy skyline, emphasizing the increasing pollution, while showcasing Franck's thoughtful and concerned demeanor as he connects these observations to the signs.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Create a photograph of Franck, an urbanite individual who thrives on the city's energy despite struggling with pollution. Depict him as an avid runner training for marathons, running up the windy streets of Montmartre in the early mornings and late evenings. Capture the serene yet vibrant atmosphere of Montmartre, showcasing Franck finding his escape from the city's exhaust while embracing its dynamic environment.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene highlighting areas in Paris heavily trafficked by cars, where Franck focuses on pollution. Show major autoroutes, the Périphérique, Châtelet in the city center, the Champs Elysées, major shopping centers, and the central business district of La Défense in the suburbs. Depict these areas bustling with people and vehicles, emphasizing the congestion and pollution. Capture the density of cars and pedestrians, illustrating Franck's belief that the high traffic volume assures these places are polluted. Highlight the contrast between the busy, polluted areas and the clear sky above.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck in his large office building with curtain wall glass and minimally operable windows. Depict a busy office environment with many people working and eating, contributing to the stagnant air. Show Franck looking uncomfortable due to the lack of fresh air and inadequate ventilation system struggling to keep the place cool. Emphasize the closed windows and the feeling of air not being refreshed, capturing Franck's sense of discomfort and the challenge of maintaining clean air in such a setting.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: A photorealistic scene of a man running through the picturesque neighborhood of Montmartre in Paris. It's early morning, with the soft light of dawn casting a gentle glow on the cobblestone streets. He is seen running along major boulevards with minimal traffic, transitioning to the charming, narrow, and windy streets that climb up the hills of Montmartre. The scene features iconic staircases scattered throughout the area, with a few classic Parisian buildings in the background. The air appears crisp and clean, suggesting the early hour. The man looks focused and determined, dressed in simple running gear. The overall atmosphere is serene and peaceful, with the beauty of Montmartre captured in great detail.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck in his youngest daughter's bedroom, visibly shaken by the previous air quality issues. Show him checking the room with a concerned expression, emphasizing the importance of clean air for his susceptible daughter. Highlight the VMC ventilation system installed in the house, with Franck ensuring it is always running. Depict the system's intake vents and controls, symbolizing its role in pulling dust out of the air and maintaining a clean environment. Capture the sense of vigilance and care Franck exercises to ensure the air in their home is well-filtered and safe.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Create a photograph of Franck, an urbanite individual who thrives on the city's energy despite struggling with pollution. Depict him as an avid runner training for marathons, running up the windy streets of Montmartre in the early mornings and late evenings. Capture the serene yet vibrant atmosphere of Montmartre, showcasing Franck finding his escape from the city's exhaust while embracing its dynamic environment.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck at the end of a strenuous run, visibly struggling with the effects on his body. Show Franck nearing the point of fainting, bent over with hands on his knees, trying to catch his breath. Capture the look of distress and exhaustion on his face, with beads of sweat and a flushed, burning expression. Emphasize the feeling of being smothered and unable to breathe properly, illustrating the intense physical discomfort he describes. Surround Franck with a natural setting, but focus on his immediate physical struggle and the sense of aggression he feels from the overwhelming effort.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck in his car at La Défense, Paris’ central business district. Show Franck sitting comfortably in his car with the windows rolled up, providing a sense of protection from the polluted air outside. Depict the modern architecture of La Défense, with busy streets and traffic surrounding the area. Capture Franck's content expression as he prepares to drive directly to the mall, avoiding exposure to the outdoor air. Emphasize the contrast between the safety he feels inside his car and the polluted environment outside.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck reflecting on his sensitivity to pollution when stressed, contrasted with a particularly relaxed day in August two years ago. Depict Franck and his wife driving around central Paris during a pollution alert (pic). Show them easily finding free parking spaces, adding to their relaxed and happy mood. Illustrate the normally bothersome heat and pollution being less noticeable to Franck due to his relaxed state. Capture the serene and joyful atmosphere, with a background of Parisian streets bathed in warm summer light, subtly hinting at the pollution in the air.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck inspecting his youngest daughter's room for air quality issues. Show Franck touching a cold, moist wall with visible large black mold spots. Capture his concern and determination as he examines the wall. Include details of the room, highlighting areas where the bad, damp, moldy air developed. Show the replaced wall with improved air quality, but subtly hint at the returning discoloration, suggesting a possible leak from the roof. Emphasize the challenge Franck faces in maintaining a healthy environment for his daughter with respiratory difficulties.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck stepping out of his apartment into a courtyard on a day with a 'medium, slightly elevated' pollution rating. Show Franck looking straight up at the clear blue sky, surrounded by the buildings of Paris. Capture his expression of contentment as he remarks, 'Such a pretty day, there’s no pollution.' Emphasize the contrast between his abstract knowledge of pollution and his immediate perception of the clear, beautiful day, with subtle cues of urban life around him.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene contrasting two different train lines managed by Franck. Show the train line with the new trains added 3 years ago, featuring large windows, lots of natural light, bright colors, and TV screens. Capture the luminous, upbeat atmosphere, with happy staff and satisfied clients, highlighting the spacious and pleasant feel. In contrast, depict the RER A & B lines, often underground, with dark, oppressive conditions. Show these trains crowded with people, dirty, old, and smelly, emphasizing the stark difference in the atmosphere and Franck's sensitivity to light and space.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck focusing on his desire for a smart purifying window and air purifier. Show a modern, well-lit room with large windows equipped with integrated air purifiers, symbolizing purified air throughout the home. Include a sleek, futuristic air purifier in the corner, providing real-time data on air quality to assure Franck of what he is breathing. Highlight his preference for a sanitized environment that cleans itself, with automated systems. Also, depict wood flooring, emphasizing Franck’s trust in these solutions due to their proven efficacy. Capture his sense of relief and satisfaction in the clean, self-regulating environment.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Create a photograph of Franck, an avid runner in Paris, who has become increasingly concerned about the city's pollution. Show Franck running with his friends, highlighting his awareness of the need to avoid polluted areas. Include a scene of his youngest daughter, who developed chronic bronchitis due to pollution, with Franck looking worried and protective. Capture the urban environment of Paris, hinting at the pollution, and emphasize Franck's concern for the air quality his daughters might face in the future.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck looking out of a window on a clear day, pointing out features on the landscape. Show a low ring of haze in the distance, contrasting with the blue sky visible through most of the window. Capture Franck’s expression as he explains, 'That’s pollution. But it’s out there in the suburbs, not here. Here there’s no pollution--it’s a great day.' Emphasize the clarity and brightness of the immediate surroundings, with a subtle haze on the horizon, illustrating the difference in air quality between the city center and the suburbs.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck driving in his car, feeling protected from pollution. Show the interior of the car equipped with a high-tech air regeneration system. Illustrate Franck's belief in the system's ability to block 3/4 of the pollution, providing him with a sense of security. Depict him relaxed and unconcerned as he drives through flowing traffic, not noticing the air quality. Contrast this with a moment of mild frustration during a traffic jam, where his primary concern is being late rather than pollution. Capture the subtle difference in his demeanor between flowing traffic and a traffic jam, emphasizing his focus on time over air quality.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck inspecting his youngest daughter's room for air quality issues. Show Franck touching a cold, moist wall with visible large black mold spots. Capture his concern and determination as he examines the wall. Include details of the room, highlighting areas where the bad, damp, moldy air developed. Show the replaced wall with improved air quality, but subtly hint at the returning discoloration, suggesting a possible leak from the roof. Emphasize the challenge Franck faces in maintaining a healthy environment for his daughter with respiratory difficulties.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene showing a concerned father and mother caring for their young daughter with chronic bronchitis. Depict them changing sheets and fabrics in her room, trying to alleviate her symptoms. Show their frustration when these efforts don't work, and their realization that it might be due to pollution. Illustrate the father taking his daughter to a doctor, who confirms her sensitivity to pollution, explaining that her illness worsens during high pollution periods. Highlight the emotional moment of understanding and concern in a well-lit, realistic medical setting.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck at a major train station, such as those hosting TGVs, focusing on the quality of indoor air. Show the architectural grandeur of the 19th-century station with large open spaces, open doors, and an open train shed. Depict Franck appreciating the fresh air and the better air circulation due to the openness of the station. Highlight the contrast with confined, closed spaces by emphasizing the airy and well-ventilated environment of the train station, capturing the sense of relief and comfort Franck feels in this setting.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck looking out of a window on a clear day, pointing out features on the landscape. Show a low ring of haze in the distance, contrasting with the blue sky visible through most of the window. Capture Franck’s expression as he explains, 'That’s pollution. But it’s out there in the suburbs, not here. Here there’s no pollution--it’s a great day.' Emphasize the clarity and brightness of the immediate surroundings, with a subtle haze on the horizon, illustrating the difference in air quality between the city center and the suburbs.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: A photorealistic scene of a man stepping off a train at a small, less crowded station. The setting is a quiet, early morning with the soft glow of the dawn light illuminating the scene. He begins walking through a charming, lesser-known neighborhood, characterized by narrow, cobblestone streets and quaint, old buildings. The atmosphere is calm and serene, with minimal traffic and few pedestrians. The man appears relaxed, enjoying his stroll through these hidden streets. The air seems noticeably cleaner, giving a sense of freshness and purity compared to the busier, more polluted areas. The overall scene captures the tranquility and charm of this off-the-beaten-path neighborhood, highlighting the man's appreciation for the cleaner, quieter streets.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck in various indoor spaces within the city. Show Franck enjoying the air in well-ventilated stores and malls, feeling comfortable and content. Highlight his preference for air-conditioned environments. Contrast this with scenes where Franck struggles with indoor spaces that have poor air circulation and too many people. Depict him in crowded public transit like suburban trains and metro, as well as in cinemas and theatres with stuffy, unrenewed air. Capture his discomfort in these poorly ventilated environments, emphasizing the difference in air quality and his reactions.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck driving in his car, feeling protected from pollution. Show the interior of the car equipped with a high-tech air regeneration system. Illustrate Franck's belief in the system's ability to block 3/4 of the pollution, providing him with a sense of security. Depict him relaxed and unconcerned as he drives through flowing traffic, not noticing the air quality. Contrast this with a moment of mild frustration during a traffic jam, where his primary concern is being late rather than pollution. Capture the subtle difference in his demeanor between flowing traffic and a traffic jam, emphasizing his focus on time over air quality.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck and his friends during a run, discussing their shared mantra about air pollution: 'Few cars, few people, few problems.' Depict them running on a quiet, tree-lined path with few cars and people around, highlighting the clean air and pleasant environment. Contrast this with another scene of a busy, heavily trafficked street filled with cars, illustrating Franck's mental model that more cars mean more pollution. Capture the clear and vibrant atmosphere of the less trafficked area, emphasizing the difference in air quality compared to the congested streets.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck emerging from the shower, visibly concerned about the air quality. Show the bathroom filled with steam and humidity, capturing his discomfort and dislike for the damp air. Illustrate Franck opening a window or turning on an exhaust fan to air out the space, emphasizing his efforts to remove the humidity. Include details of the bathroom, such as a foggy mirror and moisture on the walls, highlighting the need for better air quality. Depict Franck's concern for his daughter as the major beneficiary of these efforts, while also showing his personal discomfort with the humid air.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck and his wife in their home, focusing on their daily routine to ensure fresh air and pleasant smells. Show them opening windows to air out the house, using products like Febreze, candles, and sprays to maintain a nice scent. Depict a cozy, well-lit interior with a sense of cleanliness and freshness. Illustrate their effort to avoid stuffiness, emphasizing their desire to 'keep the freshness' in their home. Include a subtle hint of their ideal air quality by showing a view of mountains through the window, symbolizing the 'fresh but not cold' air they aspire to have.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck and his family thoroughly cleaning their apartment. Show them using a range of chemical cleaning products to ensure the space is free of dust and smells clean. Capture Franck spraying Febreze or another air freshener, with a content expression as the product cuts through the air. Include details like cleaning supplies and candles around the apartment, emphasizing their routine of cleaning every other week. Highlight the fresh and sanitized atmosphere in the apartment, illustrating Franck's preference for using sprays and candles to achieve clean air.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene highlighting areas in Paris heavily trafficked by cars, where Franck focuses on pollution. Show major autoroutes, the Périphérique, Châtelet in the city center, the Champs Elysées, major shopping centers, and the central business district of La Défense in the suburbs. Depict these areas bustling with people and vehicles, emphasizing the congestion and pollution. Capture the density of cars and pedestrians, illustrating Franck's belief that the high traffic volume assures these places are polluted. Highlight the contrast between the busy, polluted areas and the clear sky above.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: A photorealistic scene inside a cozy, well-decorated apartment. The early morning light filters through the open windows, casting a warm glow across the room. Franck, a meticulous man, is shown walking through the apartment, opening windows one by one. The bathroom door is slightly ajar, revealing steam from a recent shower. The atmosphere inside the apartment shifts from the humid bathroom to the fresh, clean air flowing in from outside. Details like lush indoor plants, family photos, and children's toys add to the homely feel. Franck's expression is one of contentment and routine as he performs this daily ritual. The scene captures the essence of a caring father and husband dedicated to ensuring a healthy living environment, deeply influenced by his childhood habits and concern for his family's well-being.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4 : Create a photograph of Franck, an ebullient, optimistic, and sociable Team Manager of train conductors on [redacted for anonymity]. Capture him in his uniform, possibly interacting with his team or passengers. Set the scene in Paris’ [redacted for anonymity]. Show Franck’s wife and two daughters [redacted for anonymity] who have grown accustomed to the area after initially fearing it. Highlight their large, sunlit apartment with a view of Montmartre in the background, and include the lively atmosphere of their neighborhood.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck in various indoor spaces within the city. Show Franck enjoying the air in well-ventilated stores and malls, feeling comfortable and content. Highlight his preference for air-conditioned environments. Contrast this with scenes where Franck struggles with indoor spaces that have poor air circulation and too many people. Depict him in crowded public transit like suburban trains and metro, as well as in cinemas and theatres with stuffy, unrenewed air. Capture his discomfort in these poorly ventilated environments, emphasizing the difference in air quality and his reactions.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck reflecting on his realization about air pollution. Show him driving on the Périphérique, noticing the traffic signs about pollution, which marked the moment he began paying attention to air quality. Illustrate a flashback of Franck experiencing trouble breathing, his eyes stinging and tearing up, and having a stuffy nose before seeing the signs. Depict the signs confirming his symptoms were due to pollution. Capture Franck's thoughtful expression as he connects his physical discomfort to the pollution warnings, with a hazy cityscape in the background.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck at a smaller, local metro station, contrasting it with the major train stations. Show the dark and dirty environment of the metro station, with dim lighting, visible rats, and unpleasant 'poison' smells. Depict Franck's discomfort and unease in this setting. Illustrate the dirt and lack of light affecting his appreciation of the space. Also, include a scene of the two main RER lines (A & B), emphasizing their underground, dark, and dirty conditions. Capture the depressing experience Franck describes, highlighting the stark difference between these smaller stations and the larger, open train stations.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of La Défense, Paris’ central business district located just west of the city, emphasizing Franck's concerns about air pollution. Show the modern skyscrapers and busy streets filled with cars, particularly highlighting the volume of traffic driving underneath the business district. Depict Franck standing outdoors, visibly uncomfortable and struggling to breathe due to the polluted air. Contrast this with the interior of the malls or offices where people seem unaffected and unaware of the pollution outside. Capture the stark difference between the indoor and outdoor environments, emphasizing the intolerable air quality outdoors.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck sitting at his desk, rating himself a 7/10 in terms of awareness around air pollution. Show his computer screen and smartphone displaying various media sources such as Météo France, Les 20h, Infos Traffic, Sytadin, Wikipedia, and the Ministry of Public Health, which he consults once a week to get a sense of the air pollution for the coming week. Illustrate the gaps in his knowledge by depicting a calendar with weather variations he overlooks. Highlight exceptions where Franck checks more regularly, such as when his daughters have a school trip or when he plans to go for a run on the weekend. Capture his thoughtful expression as he considers air quality for these specific occasions.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck and his friends during a run, discussing their shared mantra about air pollution: 'Few cars, few people, few problems.' Depict them running on a quiet, tree-lined path with few cars and people around, highlighting the clean air and pleasant environment. Contrast this with another scene of a busy, heavily trafficked street filled with cars, illustrating Franck's mental model that more cars mean more pollution. Capture the clear and vibrant atmosphere of the less trafficked area, emphasizing the difference in air quality compared to the congested streets.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: A photorealistic scene of a man, Franck, standing next to a bike-sharing station in a bustling city, wearing a mask designed to protect against pollution. It's a busy day with heavy traffic, and the air appears slightly hazy, indicating high pollution levels. Franck looks contemplative, holding a Vélib bike while checking the air quality. Nearby, people are seen commuting in various ways--some walking, others on bikes, and cars congesting the streets. The urban environment is detailed, with tall buildings, street signs, and a mix of modern and historical architecture. Franck's mask and the context of his surroundings highlight his concern for air quality and the practical measures he takes to protect himself. The scene captures the modern-day challenges of urban commuting amidst pollution.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck in a crowded indoor space, feeling uncomfortable due to the lack of air movement and renewal. Show him in a setting such as a busy public transit system, a crowded cinema, or a packed theatre. Illustrate the stifling atmosphere with many people around, making the air feel hot and stagnant. Capture Franck's body language, reflecting a suffocating feeling similar to experiencing outdoor pollution on a hot day. Emphasize his discomfort and the sense of 'not clean air' in these poorly ventilated environments.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck stepping out of his apartment into a courtyard on a day with a 'medium, slightly elevated' pollution rating. Show Franck looking straight up at the clear blue sky, surrounded by the buildings of Paris. Capture his expression of contentment as he remarks, 'Such a pretty day, there’s no pollution.' Emphasize the contrast between his abstract knowledge of pollution and his immediate perception of the clear, beautiful day, with subtle cues of urban life around him.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene highlighting areas in Paris heavily trafficked by cars, where Franck focuses on pollution. Show major autoroutes, the Périphérique, Châtelet in the city center, the Champs Elysées, major shopping centers, and the central business district of La Défense in the suburbs. Depict these areas bustling with people and vehicles, emphasizing the congestion and pollution. Capture the density of cars and pedestrians, illustrating Franck's belief that the high traffic volume assures these places are polluted. Highlight the contrast between the busy, polluted areas and the clear sky above.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck in various indoor spaces within the city. Show Franck enjoying the air in well-ventilated stores and malls, feeling comfortable and content. Highlight his preference for air-conditioned environments. Contrast this with scenes where Franck struggles with indoor spaces that have poor air circulation and too many people. Depict him in crowded public transit like suburban trains and metro, as well as in cinemas and theatres with stuffy, unrenewed air. Capture his discomfort in these poorly ventilated environments, emphasizing the difference in air quality and his reactions.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck in his youngest daughter's bedroom, visibly shaken by the previous air quality issues. Show him checking the room with a concerned expression, emphasizing the importance of clean air for his susceptible daughter. Highlight the VMC ventilation system installed in the house, with Franck ensuring it is always running. Depict the system's intake vents and controls, symbolizing its role in pulling dust out of the air and maintaining a clean environment. Capture the sense of vigilance and care Franck exercises to ensure the air in their home is well-filtered and safe.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck visiting his friends' house in the mountains, experiencing great air quality. Show Franck and his friends returning from an invigorating all-day walk, surrounded by beautiful mountain scenery. Capture the moment they arrive at the house, filled with fresh mountain air. Depict Franck and his friends opening the windows, breathing deeply, and feeling rejuvenated. Highlight the contrast between the expected fatigue and their actual sense of rest and revitalization. Emphasize the clear, crisp mountain air and the serene, natural environment contributing to their well-being.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck enjoying various green spaces and parks in Paris. Depict him in some of his favorite places, such as Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, Bois de Vincennes, Luxemburg Gardens, and Montmartre. Show Franck smiling and relaxed, surrounded by lush greenery, tall trees, and vibrant wildlife like squirrels and small animals. Capture the sense of safety and enjoyment he feels in these natural environments, emphasizing the trees providing oxygen and the presence of wildlife that reassures him of the area's cleanliness and life. Highlight the serene and protected atmosphere of these parks, illustrating Franck's belief in their ability to protect him from pollution and provide a risk-free, enjoyable experience.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4 : Create a photograph of a family who travels regularly thanks to the wife’s job [redacted for anonymity]. Show them enjoying their time in Martinique every winter, capturing lush tropical landscapes, vibrant local culture [redacted for anonymity]. Also, depict scenes of them in various international destinations, showcasing famous landmarks and diverse cities to emphasize their global adventures and frequent travels.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck driving on the Périphérique with his family, passing by the large Syctom trash treatment plant southeast of Paris. Show the smoke stacks constantly emitting smoke, with a suffocating odor noticeable to the family in the car. Capture Franck's concerned expression as he looks at the visible pollution. Illustrate the smoke disappearing into the air, raising questions about its content and effects. Emphasize Franck's frustration with the lack of public information about the pollutants being emitted and their potential health impacts. Depict signs or visual elements that hint at the need for transparency and scientific explanations about the pollutants to reassure the public.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: A photorealistic scene depicting the concept of long-term exposure to pollution and its potential health impacts. The foreground features a man standing in a busy urban environment, with a look of concern and contemplation. The air around him appears slightly hazy, indicating pollution. In the background, faint, ghostly images of various risk factors--like smoking, industrial emissions, and heavy traffic--are subtly integrated into the cityscape, symbolizing the myriad sources of lung cancer. The scene captures the invisible and insidious nature of these risks, with elements like a hospital in the distance and a shadowy figure representing illness. The overall mood is somber, emphasizing the helplessness and uncertainty people face in managing their exposure to such diseases over time, despite their vigilance. The image conveys a strong message about the long-term, often invisible threats of air pollution and other risk factors.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck reflecting on his sensitivity to pollution when stressed, contrasted with a particularly relaxed day in August two years ago. Depict Franck and his wife driving around central Paris during a pollution alert (pic). Show them easily finding free parking spaces, adding to their relaxed and happy mood. Illustrate the normally bothersome heat and pollution being less noticeable to Franck due to his relaxed state. Capture the serene and joyful atmosphere, with a background of Parisian streets bathed in warm summer light, subtly hinting at the pollution in the air.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck driving his car, feeling protected from pollution. Show Franck inside his car, looking relaxed and comfortable. Emphasize the car's advanced ventilation system and the clean, fresh air inside. Illustrate the contrast with the polluted environment outside the car, possibly showing smog or heavy traffic. Capture Franck's expression of contentment, as if he is in a protective bubble, feeling shielded from the majority of the pollution. Highlight the sense of safety and isolation from external pollutants provided by his car's circulation system.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of a concerned father learning about his daughter's sensitivity to pollution and the potential long-term health risks. Show the father lovingly reassuring his daughters, talking about taking them to places with clean air. Illustrate moments of the family in pristine, pollution-free environments, such as lush forests and clear beaches, highlighting the father's determination to provide clean air as though it were a precious gift. Capture the emotional bond and the father's protective nature, emphasizing the importance of clean air for his daughters' health.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck and his friends during a run, discussing their shared mantra about air pollution: 'Few cars, few people, few problems.' Depict them running on a quiet, tree-lined path with few cars and people around, highlighting the clean air and pleasant environment. Contrast this with another scene of a busy, heavily trafficked street filled with cars, illustrating Franck's mental model that more cars mean more pollution. Capture the clear and vibrant atmosphere of the less trafficked area, emphasizing the difference in air quality compared to the congested streets.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: A photorealistic scene of a man standing on a busy city street, looking content and comfortable while wearing a Nose Filter. The city environment is vibrant with moderate traffic, pedestrians, and a mix of modern and historical buildings. The air quality appears clean, suggesting an effective solution to pollution. Franck, the man in focus, is seen inserting the small, discrete Nose Filter into his nostrils, demonstrating its practicality. He has a slight smile, indicating his satisfaction with this innovative and unobtrusive device. The scene captures the blend of modern technology and urban living, highlighting the ease and efficacy of the Nose Filter in daily life.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck enjoying various green spaces and parks in Paris. Depict him in some of his favorite places, such as Parc des Buttes-Chaumont, Bois de Vincennes, Luxemburg Gardens, and Montmartre. Show Franck smiling and relaxed, surrounded by lush greenery, tall trees, and vibrant wildlife like squirrels and small animals. Capture the sense of safety and enjoyment he feels in these natural environments, emphasizing the trees providing oxygen and the presence of wildlife that reassures him of the area's cleanliness and life. Highlight the serene and protected atmosphere of these parks, illustrating Franck's belief in their ability to protect him from pollution and provide a risk-free, enjoyable experience.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck in his car at La Défense, Paris’ central business district. Show Franck sitting comfortably in his car with the windows rolled up, providing a sense of protection from the polluted air outside. Depict the modern architecture of La Défense, with busy streets and traffic surrounding the area. Capture Franck's content expression as he prepares to drive directly to the mall, avoiding exposure to the outdoor air. Emphasize the contrast between the safety he feels inside his car and the polluted environment outside.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of La Défense, Paris’ central business district located just west of the city, emphasizing Franck's concerns about air pollution. Show the modern skyscrapers and busy streets filled with cars, particularly highlighting the volume of traffic driving underneath the business district. Depict Franck standing outdoors, visibly uncomfortable and struggling to breathe due to the polluted air. Contrast this with the interior of the malls or offices where people seem unaffected and unaware of the pollution outside. Capture the stark difference between the indoor and outdoor environments, emphasizing the intolerable air quality outdoors.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck and his colleagues in a large office building with curtain wall glass and minimally operable windows. Show them struggling with the stagnant air, particularly when someone cooks their lunch. Depict colleagues trying to open the windows to let the smell out, with a few windows ajar. Illustrate them leaving the windows open 2-3 times per week to air out the building. Emphasize the effort to refresh the air in the office, capturing the sense of inadequate ventilation and the need for better air renewal and cleanliness.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck in a crowded indoor space, feeling uncomfortable due to the lack of air movement and renewal. Show him in a setting such as a busy public transit system, a crowded cinema, or a packed theatre. Illustrate the stifling atmosphere with many people around, making the air feel hot and stagnant. Capture Franck's body language, reflecting a suffocating feeling similar to experiencing outdoor pollution on a hot day. Emphasize his discomfort and the sense of 'not clean air' in these poorly ventilated environments.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck surrounded by various informational sources on air pollution at his desk, including websites and news media. Show his concerned expression as he reviews the data. Highlight his frustration with the lack of detailed scientific information by depicting incomplete or vague reports about the specific chemicals and their associated risks. Illustrate the complexity and confusion in his mind, emphasizing the need for precise, corroborated scientific data that can help people make informed decisions about air quality and health risks.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck running in a cold, crisp environment. Show Franck jogging along a scenic path, surrounded by a clear, chilly atmosphere that brings him well-being. Capture the invigorating effect of the cold air as he runs, with visible breath and a look of vitality on his face. Emphasize the sense of freshness and the positive impact on his lungs and overall breathing. Highlight the natural beauty of the setting, possibly with frosty vegetation and a clear sky, illustrating Franck's cherished feeling of taking in something good for his body and the effortless, beneficial breathing experience.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Create a photograph of Franck, who, despite his concerns about pollution, continues to live life to the fullest. Show him making a conscious effort to avoid pollution, such as taking his daughters to the beach or the mountains. Capture scenes of the family enjoying clean, natural environments, highlighting their joy and relaxation away from the urban pollution. Emphasize Franck's dedication to providing healthier opportunities for his daughters while maintaining a vibrant and active lifestyle.

Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4: Photorealistic scene of Franck stepping out of his apartment into a courtyard on a day with a 'medium, slightly elevated' pollution rating. Show Franck looking straight up at the clear blue sky, surrounded by the buildings of Paris. Capture his expression of contentment as he remarks, 'Such a pretty day, there’s no pollution.' Emphasize the contrast between his abstract knowledge of pollution and his immediate perception of the clear, beautiful day, with subtle cues of urban life around him.

![Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4 :

Create a photograph of Franck, an ebullient, optimistic, and sociable Team Manager of train conductors on [redacted for anonymity]. Capture him in his uniform, possibly interacting with his team or passengers.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/616566ffdc97fd0c3fdf0f68/e7e13c4c-e6b6-4ba1-96b2-91f1cac008e5/d.ww__Create_a_photograph_of_Franck_an_ebullient_optimistic_and_ee42ee45-8fe3-4df4-b6d0-151086dc90cb.png)

![Midjourney prompt generated by GPT-4 :

Create a photograph of a family who travels regularly thanks to the wife’s job [redacted for anonymity]. Show them enjoying their time in Martinique every winter, capturing lush tropical landscapes, vibrant loc](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/616566ffdc97fd0c3fdf0f68/021dcbbd-ebfb-4ea8-a7bc-b633dfdc252b/d.ww__Create_a_photograph_of_a_family_who_travels_regularly_tha_16b1a2e1-386a-42dc-8e34-369ac2064301.png)