Riding with Heidegger: A New Perspective on the Premium Vehicle

By Benjamin AhnertThe car has been the subject of social scientific research for decades. Scholars have described the empowerment people feel through the physical sensations of speed and acceleration. The ability of the premium vehicle to express status has been a staple of literature on signaling and social stratification.

These days, even in emerging markets, premium vehicles are no longer scarce. In 2013 the German and British premium brands already operated 1,085 dealerships in China; by 2020 an estimated 300 million Chinese will be able to afford premium vehicles. Meanwhile, congestion is increasingly severe. Between 2005 and 2013, the number of vehicles in China rose at a CAGR of 19%, yet the length of Chinese roads rose at just 3.4%. Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou have less than 1 km of road per one 1000 inhabitants, around one-fifth the amount in congested London and New York.

Photo by Jing Zhang

In the face of these changes, a client sought our help to reinvestigate the meaning of premium mobility beyond status and speed. We found that despite the social aura that possession of a premium vehicle still confers, the value it adds to people’s everyday lives is limited. This discrepancy required us to look for new theoretical frameworks. We found inspiration for our analysis of the limitations of the premium vehicle in Heidegger’s work on “dwelling”. By redefining premium vehicles as dwellings, we can find new ways for them to be meaningful within people’s lives.

Research approach:

A dimensional mapping of the vehicle ecology

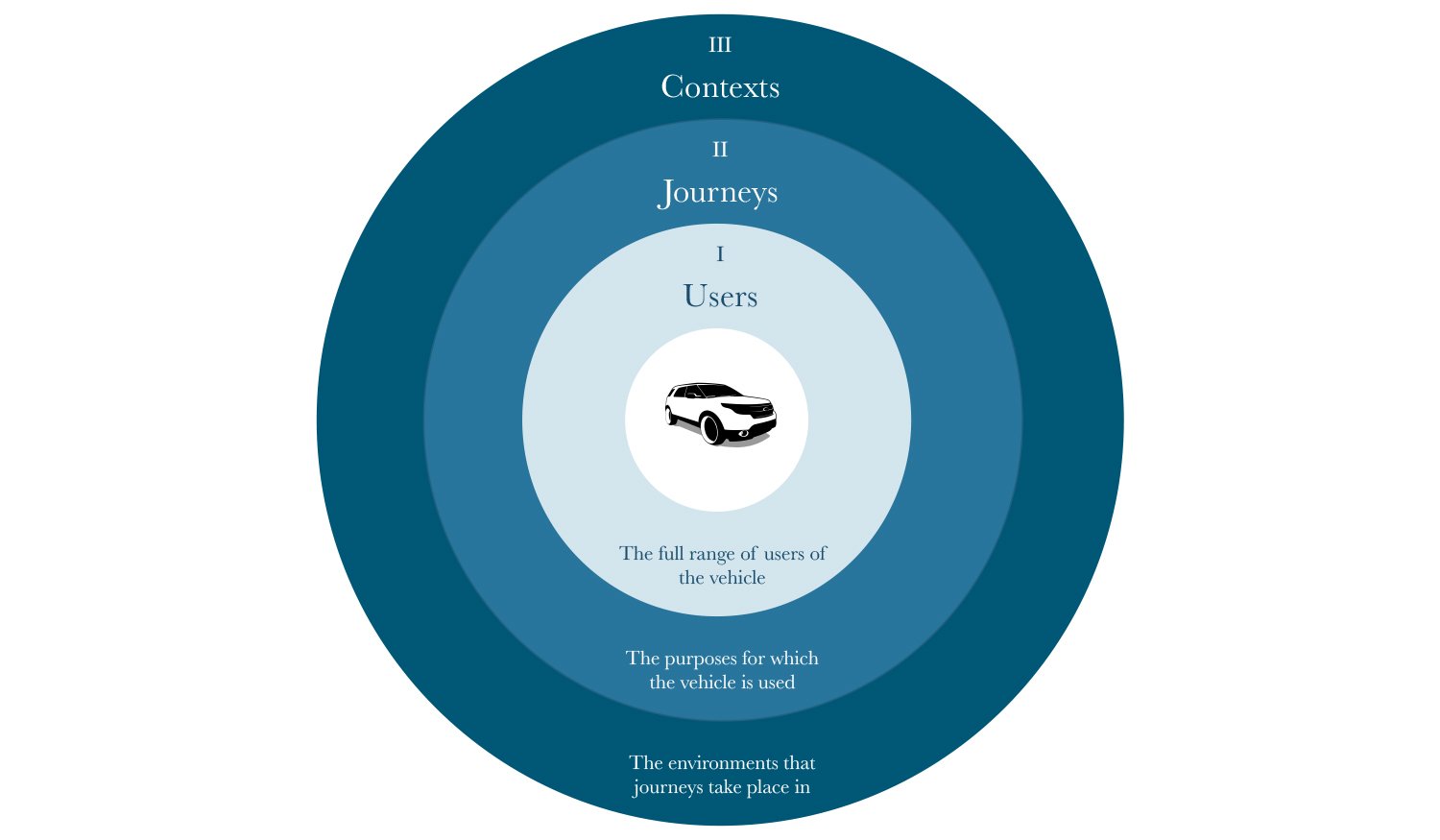

To identify where and why premium vehicles currently fall short of people’s needs we devised a research design that reflects the complexity of everyday life, using the car itself as the focal point.

The first research dimension is the different drivers and passengers of the vehicle and the social constellations and interactions emerging between them. The second dimension is the different types of journeys peoples make: different ride types; their life contexts before and after the journey, activities before, during, after ride.

Putting the vehicle at the centre of our research design enables an in-depth investigation into users, journeys, and contexts.

Concretely, this meant meeting three to five times with each vehicle, capturing daily routines and weekends, mornings and evenings and drives throughout the day, different social constellations and driving occasions when people were trying to be productive and while leisure was the priority.

Premium vehicles today hold enormous symbolic value but fail to be meaningful spaces in the everyday

We were not surprised that find cars hold enormous symbolic value for people. Undoubtedly a premium car still acts as a signifier of status. But to a married Chinese man, the car is also the only private space outside the control of parents in law, wife, or boss. To the Chinese woman trying to build a career despite gender inequality, driving is a safe haven. To the unmarried Indian, the car is where they can socialize without the constraints of strict multigenerational homes and the nosy public sphere.

Despite these added benefits of the car, we consistently found that the time actually spent in the vehicle can be worst time in people’s days. With the exception of special occasions such as road trip vacations or weekend drives into the country, the time spent behind the wheel was something some people dreaded.

How Heidegger’s notion of dwelling helps understand problems with the vehicle space

In the explosively growing emerging market metropolis, long distances and intense congestion mean people spend several hours each day in their vehicles—hours taken away from family, exercise or work. This is particularly true for drivers of premium vehicles, often entrepreneurs and senior managers who do not just go in and out of the office in the mornings and evenings, but frequently drive to meet clients or inspect sites during the day, or to attend professional and social functions in restaurants and bars in the evenings.

To understand what happens when people are stuck in their cars, we looked to Heidegger’s concept of “dwelling”. Heidegger once wondered whether a lorry driver, “at home” on the motorway, could be said to dwell there. For Heidegger, dwellings are much more than mere spatial extensions, and are not just defined by their mathematical extension. When Heidegger encourages us to “reflect on the relationship between man and space” to better understand what is so special about actual dwellings, he reminds us that “there is not man and then also space”. Rather, our experience of space is inextricably tied to the meaning created by the physical constituents and spiritual connotations of a space.

Dwellings are “places” in the sense that they are spaces that have connections with and are defined by a physical geography surrounding them. From the dwellers’ perspective, this makes them connected to aspects of their lives outside the dwelling.

Even more important, dwellings are meaningful to their dwellers because they are part of the way they make sense of their worlds. They reflect the structures that inform their inhabitants’ place in the world and shape how those manifest themselves in daily actions.

Heidegger gives the example of an ancient Black Forrest farmhouse that is a physical manifestation of the beliefs and structures that give meaning to the lives of its dwellers. It is “designed for the different generations under one roof the character of their journey through time”:

“It placed the farm on the wind-sheltered mountain slope, looking south close to the spring. It gave it the wide overhanging shingle roof whose proper slope bears up under the burden of snow, and that, reaching deep down, shields the chambers against the storms of the long winter nights. It did not forget the altar corner behind the community table; it made room in its chamber for the hallowed places of childbed and the “tree of the dead”—for that is what they call a coffin there.”

We do not, of course, suggest turning cars into rolling Black Forrest farmhouses. Yet it struck us how this notion of a place to “dwell” stands in such stark contrast to people’s experience of the vehicle space. Despite spending so much time in this space—in different social constellations, in the context of different routines, joys, and pressures—once the initial excitement of the purchase wears off, the vehicle is experienced as space extension. One involuntarily spends time in that space and tries to pass it as best as one can. Yet when people, for example, try to do work in their vehicle, today there is no natural link between the vehicle and what they are trying to do, on a practical or emotional level. In a certain sense each ride is a hack where people are trying to do something in a space that doesn’t naturally lend itself to it, that is not by itself a meaningful part of this part of one’s life.

Using Heidegger as an inspiration for redefining premium mobility as dwelling

Heidegger’s reflections on dwelling can inspire us in the design of vehicles that are not just optimized space extensions. Cars that are not merely comfortable, spacious, and quiet environments in which to bear the inevitable traffic, but places people look forward to be a part of.

But how can we know what it might actually mean for a premium vehicle to take on a more meaningful role in people’s lives?

Here the multi-dimensional vehicle ecology model can give us valuable input. Each combination of the two dimensions is a situation, with one or more people linked in a certain way using the vehicle within a certain life and environmental context. Pattern analysis on these situations allows us to distil the most important and widely shared themes from our observations of ecology situations.

Each theme speaks of the everyday aspirations people pursue within the wider context of the car ride. It shows where the vehicle fails to support daily needs for engagement and escape, professional and social challenges and diversions. These can inspire us to design ways in which the vehicle can become an essential supporter of these needs, rather than a space where we make do. With vehicles that support these experiential needs, journeys could become meaningful parts of people’s lives, great experiences that empower people to do more of what they want to do in their daily lives.

Instead of just being space to take things in and out of, the vehicle can then allow people to be a place that before, during, and after a journey is an integral productive, enjoyable, relaxing part of their lives, a place to dwell in.

This post was originally posted on EPIC's blog.