Creating An Innovation Culture

By Mikkel B. Rasmussen

The benefit is lower costs, faster processes, and higher ROI

Business Week recently published a list of the fifty most innovative companies in the world. Even though the data behind these kinds of hit lists can be dubious they always make you think “Why are we not on that list?” What’s the secret behind Apple, Google, IBM, Nike, Nokia, Toyota, and all the other much-lauded innovators on the list?

Innovation inside many of these companies is characterized by strong teamwork across disciplines, business units, and professional functions. There is a very widespread idea that innovation is driven by a lonely genius, a specific department, or a very special group of innovation champions, but this does not appear to be the case in these high-performing cultures. Instead their success seems to hinge on organizing and driving innovation through team effort and a strong sense of a shared mission.

When Nike launched its breakthrough concept Nike+ that allows runners to use their iPod as a digital coach and motivator, it was not the result of one genius in the R&D department. It was a collaborative solution developed and sharpened by marketing experts, shoe designers, software engineers, usability specialists, and people in various other disciplines. They all worked together to reach a very ambitious target in a very short time.

The same grassroots-style team effort was behind the development of Toyota’s Prius, Lego’s Mindstorms, Blizzard’s online game World of Warcraft, Google’s Ad-Sense, Johnson Controls’ world-class building service systems, Cisco’s online meeting system Telepresence, in addition to thousands of other innovations across industries and the world. It’s rare that a successful innovation is the result a single inventor or a one-person army inside a company. Most successful innovations draw on multiple perspectives: technology development, customer insight, business model development, marketing, and design. And they seem to do it simultaneously. That is: the marketing people and the R&D actually work together in high performing firms.

R&D is from Mars and marketing from Venus

A majority of successful innovations in the past ten years have been the result of a tremendous team effort bringing both R&D, design and marketing perspectives together. If team effort is the key that can unlock effective innovation why are so few companies using it? Why are marketing and R&D still working like two different cultures?

It may seem obvious to highlight the importance of R&D and marketing cooperating together effectively but it’s surprising how often these two disciplines don’t blend well with each other.

I recently visited a big pharmaceutical company and discovered that the marketing department was not only in a different building than R&D but in another city. The two units rarely met: “The people from R&D don’t understand the business fundamentals anyway,” expressed someone in marketing.

On another occasion I attended a workshop for global consumer brand, which included engineers from the R&D unit and MBAs from the marketing department. The workshop was about exploring a new business opportunity that could potentially generate a new billion-dollar business for the company. I was surprised by the lack of energy in the room and by the clearly antagonistic language that was used during the two days the workshop lasted—it was as if two historic enemies were sitting down to negotiate a peace treaty that neither really wanted. Nobody really wanted to chip in and very little time was spent on exploring the actual opportunity. The energy level only rose when the team started to talk about whose role and responsibility it was to start this particular project. The company eventually moved forward with the idea but after two years of development they pushed it to what the company calls “our corporate graveyard.” The graveyard is packed with large development projects that were far along in development but which couldn’t take the final step toward market introduction. When asked directly, the R&D managers explained the reason for the high failure rate was due to the dominance of the marketing department and its lack of support of long-term goals and discovery processes. Interestingly, the marketing people had similar ideas about the R&D department: “They are out of touch with reality and just invent technologies for the sake of technologies—they don’t respect that there is something called customers.” Both sides were probably right. Too much R&D focus will probably move the company further away from its customers needs. Too much focus on marketing will make the company vulnerable to market changes.

In our work we work closely with both marketing and R&D people and have been lucky to observe the two cultures in great detail. It is apparent that these two disciplines in many firms often exist as if they were two very different “planets,” with different reward systems, success metrics, methods, and ideas. The marketing people are often generalists who tend to see the big picture—they’re rewarded on short-term goals, they need to act now, and they’re motivated by insights that can give them answers. The R&D people, on the other hand, are very often functional specialists—they’re rewarded for long-term progress, they’re very focused on details, they’re often developing new technologies because it can be done, and they’re motivated by insights that can give them questions and puzzles to solve (see Table 1).

Table 1: marketing versus R&D - are they from Mars and Venus?

The natural routine in most companies is that R&D and marketing work with very different agendas and in very different directions. That has not been a problem as long as there was a clear division of labor. R&D has taken care of product and technology development and marketing has taken care of bringing the product to market.

The changing nature of innovation demands closer collaboration between R&D and marketing. The problem is that in many companies the very nature of innovation is changing dramatically. Innovation is no longer confined to product development. It is also a matter of creating new services, business models, partnerships, and customer experiences. The market rewards those companies that can innovate multiple dimensions simultaneously.

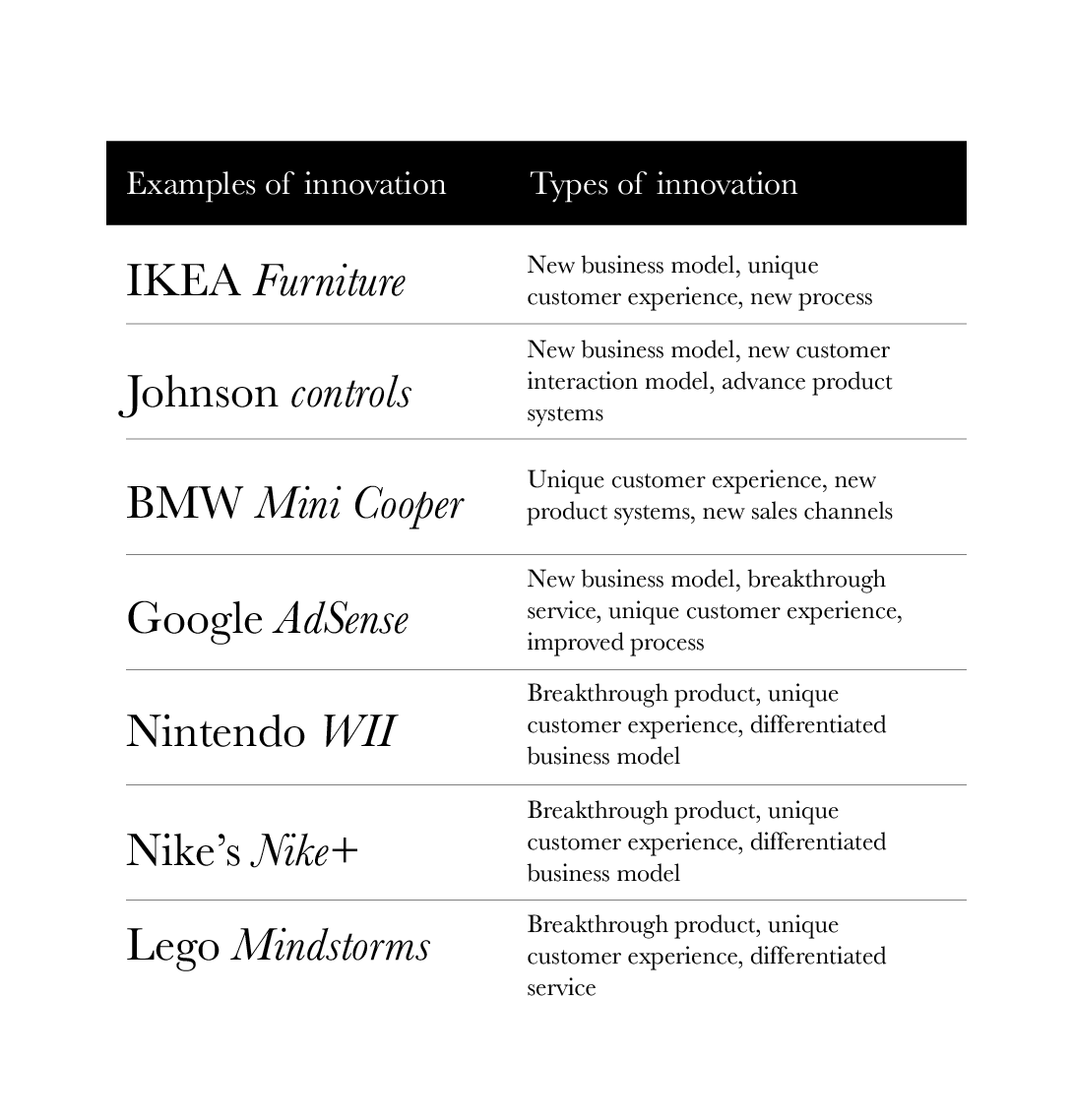

IKEA, for example, is not just successful because they have great products. The company has pioneered a new business model (low-cost, high design value), a new process (customers assemble the product), and a new customer experience (plug-and-play home design). Johnson Controls is not successful just because it has the best air conditioning products. They transformed the business model of the building component industry (from products to services), developed a new customer interaction model (helping customers optimize their buildings instead of buying components), and created a range of very advanced product systems (e.g. systems for green buildings). BMW is not only successful with their Mini Cooper because it is a great car. The car manufacturer has fundamentally changed the sales channel (a product brand with its own retail universe), the customer experience (a car that is fun), and the product systems around the car (an extensive accessories program). Companies that are good at combining different types of innovation can create what economists call “temporary monopolies” that tend to dominate a market space for a period of five to ten years.

Table 2: innovation is moving beyond product development

Expanding innovation from pure product development to other forms of innovation demands a different division of labor inside the company. You can no longer depend on R&D as the single source of innovation. R&D is for example not very good at developing compelling services, nor are they very experienced in designing business models.

This is documented in a number of studies that reveal that there is no longer a clear correlation between the investment in R&D and business performance. Some of the biggest spenders in R&D, like General Motors, are some of the poorest performers in the marketplace. Or as Apple’s Steven Jobs has expressed: “Innovation has nothing to do with how many R&D dollars you have… It’s not about money. It’s about the people you have, how you’re leading them, and how much you get it.”

This doesn’t mean R&D isn’t important anymore. But it means that the role of R&D is changing. Instead of being the primary source of innovation it is now one among several innovation channels. It also means that more people across the organization should be involved in innovation. That probably requires fewer steep boundaries between R&D and marketing and it certainly requires a much higher degree of alignment and strong leadership.

Most firms still work under the assumption that innovation is mostly about improved product performance and that there needs to be a clear division of labor between units and disciplines. This can easily lead to an ineffective innovation model and a very confused organization with one or more of the following symptoms:

A slow and bureaucratic innovation process with lots of resources spent on coordination

A focus on defensive innovations and difficulties in finding game-changing projects to invest in

An innovation portfolio with “belly problems”—a majority of projects that are fully developed but not marketable

A high failure rate of larger innovation projects

No clear priorities or success criteria for selecting projects

Lack of excitement around newness and change

Making people look in the same direction

There are many ways a company can get people to buy into a shared culture of innovation. One strategy is to try to force R&D and marketing people to work together—many companies have experimented with changing the organizational structure by breaking down silos and building more flexible and project-oriented organizations. Another is to set up an incentive system that rewards collaboration. A third solution is to set up detailed protocols for innovation processes and to make sure that every single development project complies with company procedures.

These interventions might fix parts of the problem but are only icing on the cake if you’re not solving the root cause of the problem: the R&D people and the marketing people do not have the same goals or the same ideas of success—they come from different planets.

The French author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wisely said, “Love does not consist in gazing at each other but in looking together in the same direction.” The same idea can be applied to R&D and marketing together. Having a shared sense of discovery, direction and intent is often a more effective way to align people than forcing them to appreciate one other directly.

The critical ingredient is to have the entire organization on the same page on why, how, and where the company needs to innovate and to do that in a way that motivates people, energizes the teams, and leaves lots of initiative to the organization. The innovation agenda doesn’t need to be complicated. But it needs to be rich in content, consistent, and inspiring.

Setting a leadership agenda for innovation has benefits:

It becomes easier to prioritize and focus your innovation investments on fewer, more significant projects.

You can free cash and cut complexity by eliminating conflicting innovation agendas internally.

You can speed up your time to market considerably because your teams are better in sync from R&D to marketing.

It becomes easier to measure innovation impact.

Many of the highest performing innovators in the world follow this logic. Top 50 companies have introduced products, services, and customer experiences with a very strong and coherent idea—or governing principle—behind them. It becomes clear that most of these companies are on a quest to achieve something very specific and special whether it’s transforming business services (IBM), redefining how people access information (Google), creating the next-generation green vehicle (Toyota), or pushing the performance boundaries of athletes (Nike).

Setting a leadership agenda for innovation

A good innovation “intent” or plan cannot and should not be drafted during a two-day off-site workshop. Like most other innovation work, a good plan requires a rigorous thinking process and significant insights into customer needs, company capabilities, and changes in the competitive landscape. The organization also needs time to reflect and absorb the opportunities and options.

These steps can ease the process:

1. Start with the customers

Start the process by gaining insight into customer needs, as well as the contextual forces that might influence your industry in the future. It can be extremely rewarding for top managers to spend time learning about their customers’ daily lives, using that understanding to identify discontinuities and to anticipate changes in the landscape. Many times we have found that the discussions in a management group become much more valuable and inspiring when business leaders place their customers’ everyday lives at the center of the conversation. This allows you to challenge the basic assumptions in your industry and open up discussions about entirely new business opportunities.

We observed this change among the management board of a major media conglomerate, which had worked intensively to create an agenda for long-term innovation. For a long time, the group had the habit of benchmarking and comparing themselves to competitors in their industry; many of their ideas had been based on insights into what their competitors were doing. Getting some deep insights into how consumers use, choose, and feel about media content changed the discussion entirely and made it clear to the board that they were, in fact, not just competing with other media companies but were increasingly competing with players in the technology industry. The board also discovered that the role of media in people’s lives had changed fundamentally and that a large part of the company’s product portfolio was therefore losing relevance and value at a speed the company had not seen before.

2. Detect patterns and think like a good journalist

Mapping future needs and opportunities can make you feel like a kid in a candy store: there’s so much to choose from and everything looks delicious. It’s tempting to choose a little of each. Because a good leadership agenda is about prioritizing and choosing your future it requires bold choices. The trick is to detect patterns in the data and find the vectors that best align with your company’s culture and capabilities. The hard part is to choose a direction and deselect all the other options that look so tempting. In most cases the pattern-recognition process will reveal some very clear options and some surprisingly simple answers on where the future value lies. A good rule is to think like a journalist who is writing a headline for his or her story. There can only be one headline, so you’d better make sure you put the most important stuff up front.

3. Involve your organization—but only when you’re ready

An African proverb wisely states, “If you want to go fast, you can always walk alone, if you want to go far, walk together.” Creating an innovation agenda requires both walking fast and walking far. In the beginning you need to walk fast. That’s when you create insights and set the intent. If you involve too many people in the discovery process you risk compromising and allowing corporate politics to destroy what may be some very clear thinking. We’ve experienced positive results when the CEO selects a small group of the best thinkers to lay the groundwork for innovation and help set the intent. Once that’s done you need to walk far. This is the phase where the intent in translated into challenges and projects in the organization. The task of top management here is to change the traditional downward communication style to an upward communication stream of new ideas coming from the entire organization.

4. Work fast and stay determined about implementation

The full payoff from a new innovation agenda will come when you implement changes swiftly and firmly. Very often the new agenda will have rather big consequences for how you prioritize R&D investments, how you organize innovation projects, what capabilities you need to build, and how you reward entrepreneurs inside your organization. These changes have to be mapped before you launch the intent for a broader audience and should be part of the message itself. If possible, make the changes as simple to understand as possible. Prioritize interventions that cut complexity and free cash—for example, cut away investments that aren’t aligned with the intent and remove procedures that slow your time to market. Implementing the innovation agenda should feel liberating, not like your company is being occupied.

5. Learn from the politicians—tell the story again, again and again

Most people will meet a new innovation agenda with skepticism—with good reason. They need to see your commitment in action. But they also have to feel that this not just another weird campaign that will blow over in two weeks’ time. The best way to convince people about the seriousness of your intention is to be consistent and determined. Politicians know they can win voters by repeating their message again and again. You need to practice your inner politician and repeat the story again and again.

An effective way to show strong leadership is to commit to a big idea on why, how, and where the company is expected to develop and grow.

Mikkel R. Rasmussen is a partner at ReD Associates.

[Banner image by Skye Studios, via Unsplash]